Coronavirus in Context: Neurological Effects of COVID-19

Hide Video Transcript

Video Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

My guest today is Dr. Kenneth Tyler. He is Department Chair of Neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Dr. Tyler, thanks for joining me.

They were basically hospitalized patients, often a lot of comorbidity. And not surprisingly, I think what we were seeing pretty commonly in those series were the neurologic complications that would result from organ system failure or other problems.

Obviously, if you have a multi organ system failure, if you have ARDS, if you have a hyper inflammatory state or DIC, it's probably not surprising that you develop things like encephalopathy and altered mental status, an increased risk of stroke, or things like that.

And I think that's what was initially reported. And so those are the complications we tend to see in the sickest patients. And as I say, often older, often male, multiple comorbidities.

I think the more interesting ones that are starting to emerge that we still don't have a very good sense of the frequency or the distribution of, um, have to do with the fact of, we're beginning to see reports that suggest that the virus, SARS coronavirus too, can directly infect the nervous system in some patients.

And so you're just beginning to now see the first reports of things like encephalitis being caused by the coronavirus.

And we're just beginning to see some rare initial reports of that. And so again, in a classic sense, those would be patients with an altered mental status, focal neurologic features, an abnormal spinal fluid, abnormal neuroimaging. And it all seems like it fits together with viral invasion.

And then I guess my third pile, um, would be, we know from the experience with MERS and SARS that, in addition to those first two groups, we would sometimes see what I would call post infectious immune mediated complications.

And many of your reviewers may have seen some of the news stories or the original article around the recent report from Italy of Guillain Barre syndrome associated with a-- a COVID infection. And there have been--

And we know that those-- that's often been linked to other viruses. You know, some of your listeners may remember all the excitement about Zika, for example, and Guillain Barre syndrome.

And I think, um, those have been confirmed in other reports. And now the question is, how common, is it early, and is it distinctive enough that, uh, it would, say, separate out COVID-19 infection from, say, flu or other upper respiratory infections.

And it does, uh, in fact, uh, olfactory neurons or cells in the neuro olfactory neuro epithelium. And so there might be a neurologic mechanism for it. But of course, there are lots of other ways that could happen as well.

And I think the speculation that gets interesting, of course, comes from, again, those experimental models raise the question of, the nose or the oral pharynx as a way that the virus might invade the nervous system.

And does that have anything to do with, you know, the disease that we see? Including, could it, um, explain any parts of some of the respiratory involvement? Most of the papers, and my belief is that almost all of those are ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, and so it's direct infection, and then the immune response it triggers.

But it's an interesting speculation about, oh, could there be any neural dis regulation, and could that account for any of the features that, uh, we see. So we're going to have to wait on that one. It's speculation rather than fact, although the smell and taste observations seem real.

And, um, probably related both to d-- disseminated intravascular coagulation, and maybe also, um, to the just general hyper coagulable state endothelial injury. So obviously, if you're seeing an increased risk of stroke, you can get focal neurologic deficits from that.

We are seeing reports of numbness in some of the cases. And whether that is part of this-- this post viral immune mediated peripheral nervous system thing, in other words, akin to the GBS, I think we'll have to see. But again, we've now seen several reports of that. So now we need to get a little bit better data.

But what do you think is going on here? Is-- is one causing the other? Is COVID causing stroke? Are these people suffering stroke and coincidentally have COVID-19? It's an important relationship. And that's what I wanted to hear from you today. What's our best bet what's going on, especially in younger people?

So perhaps in the older population, not so surprising that if you have those risk factors and then add a hyper inflammatory state or a hyper coagulable state, that you'd see more strokes.

Um, the reports of strokes in people who don't have any of those conventional risk factors mostly tend to be anecdotal so far. But I think it's going to be really important to see, does that hold up. And if it does, um, I think, again, we're going to say that probably the mechanism is this hyper inflammatory state with this huge pulse of these different pro inflammatory cytokines, and maybe--

The other speculation has been the receptor for the virus, um, the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 is found on endothelial cells. And so there may be some direct endothelial cell injury as well.

We've talked about anti-inflammatory. As you've mentioned the inflammatory response. And there has been some conflicting data there. What's kind of your thoughts in terms of how the neurologic manifestations may impact effective therapies and-- and where we may need to look?

Of course, anything you do that inhibits the growth of the virus will ultimately be a great thing. So I'm encouraged by the early, um, remdesivir trials. And we'll have to see if those, in fact, hold up.

And similarly, we know that immunotherapy can be effective for other viruses. And so many centers around the country, including ours in Colorado, have been actively, uh, starting to treat patients with a plasma from convalescent patients.

And again, I would just caution all of your listeners, just like you did, John, that the cool thing is that all of these are going on, that they're actually in real clinical trials. And I'm hoping we're going to get some answers over the next several months.

Um, but whether any of those would be specifically advantageous for the neurologic disease, we don't know at the moment. You know, of course, the focus has really been on just the disease in general.

But the presumption is, if it's good for the disease, then it's going to be good for the reasons we've talked about, the neurology.

If people aren't coming in to the emergency room with stroke, what do you think that means? That-- that could be a very concerning sign.

So I think, on the other hand, what we have heard from, uh, our emergency department is that other medical problems, whether those are things as like appendicitis or heart disease, the patients are coming in with more severe forms of those diseases, because they've delayed appearing in the emergency room. So I think--

With certain techniques we can extend that, but we usually think in terms of four hours, six hours, something like that. And even within that window, the earlier the better. And so any delay of patients coming to the emergency room with stroke symptoms may push them outside those therapeutic windows.

And to be honest with you, once you get well outside those windows, we're almost back into the old era where, you know, the treatments were more, um, time, physical therapy, trying to prevent the next stroke than they were getting rid of that first one.

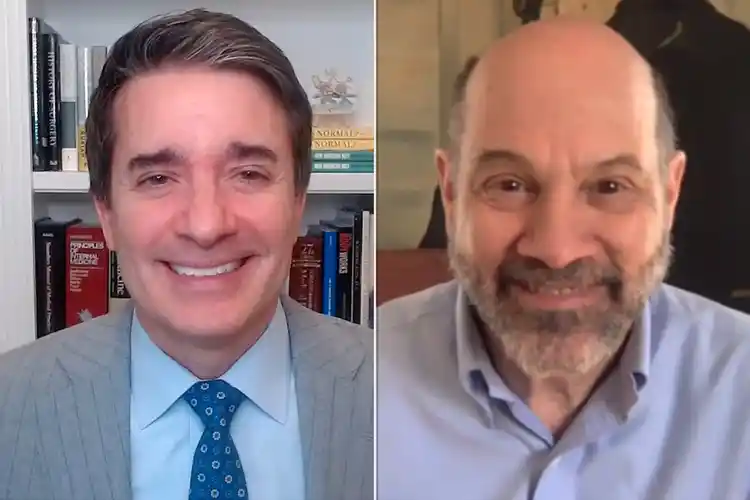

JOHN WHYTE

You're watching Coronavirus in Context. I'm Dr. John Whyte, Chief Medical Officer at WebMD. We've heard a lot about the pulmonary complications of COVID, the coronary complications. But what about the neurologic complications? My guest today is Dr. Kenneth Tyler. He is Department Chair of Neurology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. Dr. Tyler, thanks for joining me.

KENNETH TYLER

Great. Thanks for having me, John. It's a pleasure. JOHN WHYTE

What do we know about how COVID-19 affects our nervous system? KENNETH TYLER

Well John, I'd like to think about this in sort of three piles when I think about the neurologic complications of COVID-19. I think the first reports that started to come out of Wuhan, China and others involved the sickest patients. They were basically hospitalized patients, often a lot of comorbidity. And not surprisingly, I think what we were seeing pretty commonly in those series were the neurologic complications that would result from organ system failure or other problems.

Obviously, if you have a multi organ system failure, if you have ARDS, if you have a hyper inflammatory state or DIC, it's probably not surprising that you develop things like encephalopathy and altered mental status, an increased risk of stroke, or things like that.

And I think that's what was initially reported. And so those are the complications we tend to see in the sickest patients. And as I say, often older, often male, multiple comorbidities.

I think the more interesting ones that are starting to emerge that we still don't have a very good sense of the frequency or the distribution of, um, have to do with the fact of, we're beginning to see reports that suggest that the virus, SARS coronavirus too, can directly infect the nervous system in some patients.

And so you're just beginning to now see the first reports of things like encephalitis being caused by the coronavirus.

JOHN WHYTE

Explain to our viewers what encephalitis means. KENNETH TYLER

Yeah. So, uh, usually what we're trying to distinguish here is, is there a direct viral infection and injury of the nervous system. And of course, the ultimate proof of that is, um, either detecting the virus in the nervous system through, you know, where most of your viewers will be familiar with things like CSF, PCR, for herpes viruses, or other tests, and-- JOHN WHYTE

Like Western equine encephalitis? KENNETH TYLER

Yeah, yeah. So here, the virus directly infects the nervous system and either kills cells and produces symptoms because of that, or triggers an immune response, which can be deleterious to the host as well. And we're just beginning to see some rare initial reports of that. And so again, in a classic sense, those would be patients with an altered mental status, focal neurologic features, an abnormal spinal fluid, abnormal neuroimaging. And it all seems like it fits together with viral invasion.

And then I guess my third pile, um, would be, we know from the experience with MERS and SARS that, in addition to those first two groups, we would sometimes see what I would call post infectious immune mediated complications.

And many of your reviewers may have seen some of the news stories or the original article around the recent report from Italy of Guillain Barre syndrome associated with a-- a COVID infection. And there have been--

JOHN WHYTE

Where people start to become paralyzed from the bottom up, right? KENNETH TYLER

Yes. So that's-- you know, unlike those others that we've talked about, that's the central, uh, which are the central nervous system. This is the peripheral nervous system. And it's an involvement of a nerve. It's-- people get numbness, weakness, paralysis, respiratory problems, and things like that. And we know that those-- that's often been linked to other viruses. You know, some of your listeners may remember all the excitement about Zika, for example, and Guillain Barre syndrome.

JOHN WHYTE

We don't remember Zika anymore, Dr. Tyler. KENNETH TYLER

Right. And that was last year's hot news. But, uh-- JOHN WHYTE

What about loss of smell? Everyone's saying that's related to neurological implications. Is that true, this loss of smell that some folks are experiencing? KENNETH TYLER

Yeah. So I think in-- even in the original reports out of Wuhan, there was this interesting, uh, observation that a subset of patients seemed to lose smell or, um, taste, or some combination of both of them. And I think, um, those have been confirmed in other reports. And now the question is, how common, is it early, and is it distinctive enough that, uh, it would, say, separate out COVID-19 infection from, say, flu or other upper respiratory infections.

JOHN WHYTE

What do you think? Does that make sense to you? The singular loss of smell along with cough and fever is a representation of some neurological impact? What's your best bet? KENNETH TYLER

Well, I think we're still trying to figure out what is the cause of it in COVID. We know from some studies and mice and other things that this is a virus that, for example, in an experimental model, you can inoculate some forms of coronavirus in mice. And it does, uh, in fact, uh, olfactory neurons or cells in the neuro olfactory neuro epithelium. And so there might be a neurologic mechanism for it. But of course, there are lots of other ways that could happen as well.

And I think the speculation that gets interesting, of course, comes from, again, those experimental models raise the question of, the nose or the oral pharynx as a way that the virus might invade the nervous system.

And does that have anything to do with, you know, the disease that we see? Including, could it, um, explain any parts of some of the respiratory involvement? Most of the papers, and my belief is that almost all of those are ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, and so it's direct infection, and then the immune response it triggers.

But it's an interesting speculation about, oh, could there be any neural dis regulation, and could that account for any of the features that, uh, we see. So we're going to have to wait on that one. It's speculation rather than fact, although the smell and taste observations seem real.

JOHN WHYTE

Are we hearing anything about numbness and tingling? Any elements of those? Or weakness. You mentioned Guillain Barre. Like, perhaps some unilateral weakness. That-- that typically hasn't been reported. Is that true? KENNETH TYLER

I think I'd sort of say maybe a little bit. Because if you think in the-- in that first group of cases that I was telling you about, one of the things, of course, that happened, is they had an increased incidence of, uh, stroke. And, um, probably related both to d-- disseminated intravascular coagulation, and maybe also, um, to the just general hyper coagulable state endothelial injury. So obviously, if you're seeing an increased risk of stroke, you can get focal neurologic deficits from that.

We are seeing reports of numbness in some of the cases. And whether that is part of this-- this post viral immune mediated peripheral nervous system thing, in other words, akin to the GBS, I think we'll have to see. But again, we've now seen several reports of that. So now we need to get a little bit better data.

JOHN WHYTE

So folks should be alert to some of the symptoms that could be a sign. I want to talk to you about stroke and go back to that. KENNETH TYLER

Sure. JOHN WHYTE

I'm sure you're aware there are some instances of young people coming in with stroke in COVID-19. Stroke in young people is not unheard of, but still is unusual, correct? KENNETH TYLER

Yes. JOHN WHYTE

And people are talking about, when they're doing imaging, some, you know, neurologists have talked about, the clots are still forming as they image them, which is unusual. Let-- let's be honest, as we see that. But what do you think is going on here? Is-- is one causing the other? Is COVID causing stroke? Are these people suffering stroke and coincidentally have COVID-19? It's an important relationship. And that's what I wanted to hear from you today. What's our best bet what's going on, especially in younger people?

KENNETH TYLER

Yeah. I think my disclaimer is, what's true today on Monday, I might tell you something different when you interview me again next week. JOHN WHYTE

Fair enough. KENNETH TYLER

I think, again, I'd put it into some different groups. We do know that comorbidities, think diabetes, hypertension, dislipidemia, and older age, as well as being male, are all sort of risk factors for more severe COVID disease. So perhaps in the older population, not so surprising that if you have those risk factors and then add a hyper inflammatory state or a hyper coagulable state, that you'd see more strokes.

Um, the reports of strokes in people who don't have any of those conventional risk factors mostly tend to be anecdotal so far. But I think it's going to be really important to see, does that hold up. And if it does, um, I think, again, we're going to say that probably the mechanism is this hyper inflammatory state with this huge pulse of these different pro inflammatory cytokines, and maybe--

JOHN WHYTE

I was gonna ask you, cytokine storm. What role is this playing? KENNETH TYLER

Yeah, well-- yeah, exactly. And that's been thought to play a key role in the ARDS, the respiratory distress syndrome. Um, and it wouldn't be surprising. We know those same cytokines can do things like change blood brain barrier permeability and other things. The other speculation has been the receptor for the virus, um, the angiotensin converting enzyme 2 is found on endothelial cells. And so there may be some direct endothelial cell injury as well.

JOHN WHYTE

So they're primarily long based, correct? Those receptors? KENNETH TYLER

Yeah. Again, for the young people, we're thinking about, wait a minute, they don't have our standard risk factors. Folks at the hyper coagulable state, the hyper inflammatory state, or the endothelial injury. All of those things could be playing a role if, in fact, we really do see, um, these anecdotal reports of different doctors' experiences unconfirmed in the larger series. JOHN WHYTE

So taking all of this together, knowing the neurological complications as well, then where do you think we are in ineffective treatments? Because there's been discussions about on drugs that impact cytokines, but they also can have bad consequences. We've talked about anti-inflammatory. As you've mentioned the inflammatory response. And there has been some conflicting data there. What's kind of your thoughts in terms of how the neurologic manifestations may impact effective therapies and-- and where we may need to look?

KENNETH TYLER

So I think I'd start it off by saying we don't, at the moment, have any FDA-approved or, um, therapies that we know are effective. And we don't really have any therapies that have met the usual standard that neurologists expect of having been proven in a randomized controlled-- JOHN WHYTE

We're just going to let you guess. We're going to let you estimate. KENNETH TYLER

Is it OK if I say, don't use Lysol or bleach? Despite what you may have heard. JOHN WHYTE

But what-- where do you think effective therapies may end up ly-- lying? KENNETH TYLER

Yeah. I think the ones that are going to be really interesting is if we understand this mechanism of these neurologic complications. And if it looks like, for example, that the hyper inflammatory state and elevated cytokines account for some of the neurologic things like encephalopathy, then targeting those in those patients, as you alluded to, like IL6 inhibitors have gotten a lot of interest and are in trials. Of course, anything you do that inhibits the growth of the virus will ultimately be a great thing. So I'm encouraged by the early, um, remdesivir trials. And we'll have to see if those, in fact, hold up.

And similarly, we know that immunotherapy can be effective for other viruses. And so many centers around the country, including ours in Colorado, have been actively, uh, starting to treat patients with a plasma from convalescent patients.

And again, I would just caution all of your listeners, just like you did, John, that the cool thing is that all of these are going on, that they're actually in real clinical trials. And I'm hoping we're going to get some answers over the next several months.

Um, but whether any of those would be specifically advantageous for the neurologic disease, we don't know at the moment. You know, of course, the focus has really been on just the disease in general.

But the presumption is, if it's good for the disease, then it's going to be good for the reasons we've talked about, the neurology.

JOHN WHYTE

Now, I want to end, Dr. Tyler, in the last few minutes asking you about, there is good data that's showing that cases of stroke presenting to the ER are way down. You are chair of the department. Strokes occur all the time. If people aren't coming in to the emergency room with stroke, what do you think that means? That-- that could be a very concerning sign.

KENNETH TYLER

So we've been having in Colorado, you know, regular conferences with the key people in the neurology department. And I can tell you that we haven't seen that precipitous drock-- drop here. Our stroke service has, in general, been about as busy as it was before. So I think, on the other hand, what we have heard from, uh, our emergency department is that other medical problems, whether those are things as like appendicitis or heart disease, the patients are coming in with more severe forms of those diseases, because they've delayed appearing in the emergency room. So I think--

JOHN WHYTE

But you probably have heard in other centers, stroke presentations are down, which is concerning, because they can be debilitating. KENNETH TYLER

Well, and I think even, perhaps, more concerning. Because, you know, we keep on talking about the golden hour or, you know, the window of opportunity. JOHN WHYTE

Remind-- remind people what that means. KENNETH TYLER

So I think we know that many of the most effective interventions we have for stroke, of course, clot lysis, clot retraction, and things like that, that their efficacy is confined to a narrow window of time. With certain techniques we can extend that, but we usually think in terms of four hours, six hours, something like that. And even within that window, the earlier the better. And so any delay of patients coming to the emergency room with stroke symptoms may push them outside those therapeutic windows.

And to be honest with you, once you get well outside those windows, we're almost back into the old era where, you know, the treatments were more, um, time, physical therapy, trying to prevent the next stroke than they were getting rid of that first one.

JOHN WHYTE

So it's a good reminder, if folks do have symptoms of stroke, even during the setting of-- of COVID-19, they need to call 9-1-1 and get to the emergency room as soon as possible. KENNETH TYLER

I think that's a great message. And if they forget everything else I said about COVID, but remember that if you have a neurologic emergency, you should still show up in the emergency room, that would-- [AUDIO OUT] JOHN WHYTE

In a couple of seconds, tell us what those signs are. Remind our viewers those signs. KENNETH TYLER

Uh, somebody who has transient loss of vision, a transient alteration in speech, focal weakness, any of those things, especially in an older individual with risk factors, uh, should still, um, come as quickly as they can to an emergency room. JOHN WHYTE

Well, Dr. Tyler, I want to thank you for sharing your insights today. KENNETH TYLER

It's been a real pleasure and I hope to get to speak to you again, John. JOHN WHYTE

And I want to thank you for watching Coronavirus in Context. I'm Dr. John Whyte.